“I Don’t See Colour”

Colour-blindness is the belief that there are no differences between different races and ethnicities; therefore, racism does not exist. The following expressions often accompany this ideology: “We are all one human race,”

“I am not racist, I treat everyone equally,” “All lives matter,” and “I don’t see colour.”

On the surface of it, this ideology might seem like it could work. If everyone is seen as equal, how could there be racism? But the reality is racism happens every day, and this belief not only dismisses all BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour) lived experiences but also implies racism does not exist as long we ignore it.

I will share one of my experiences with racism and show how colour blindness led to poor racism awareness, inaction against racism, and mental health struggles.

Playing hockey in Newfoundland & Labrador often involved long bus rides to connect with the opposing teams. During these long hours on the bus, I was often confronted with the harshest and most relentless hate.

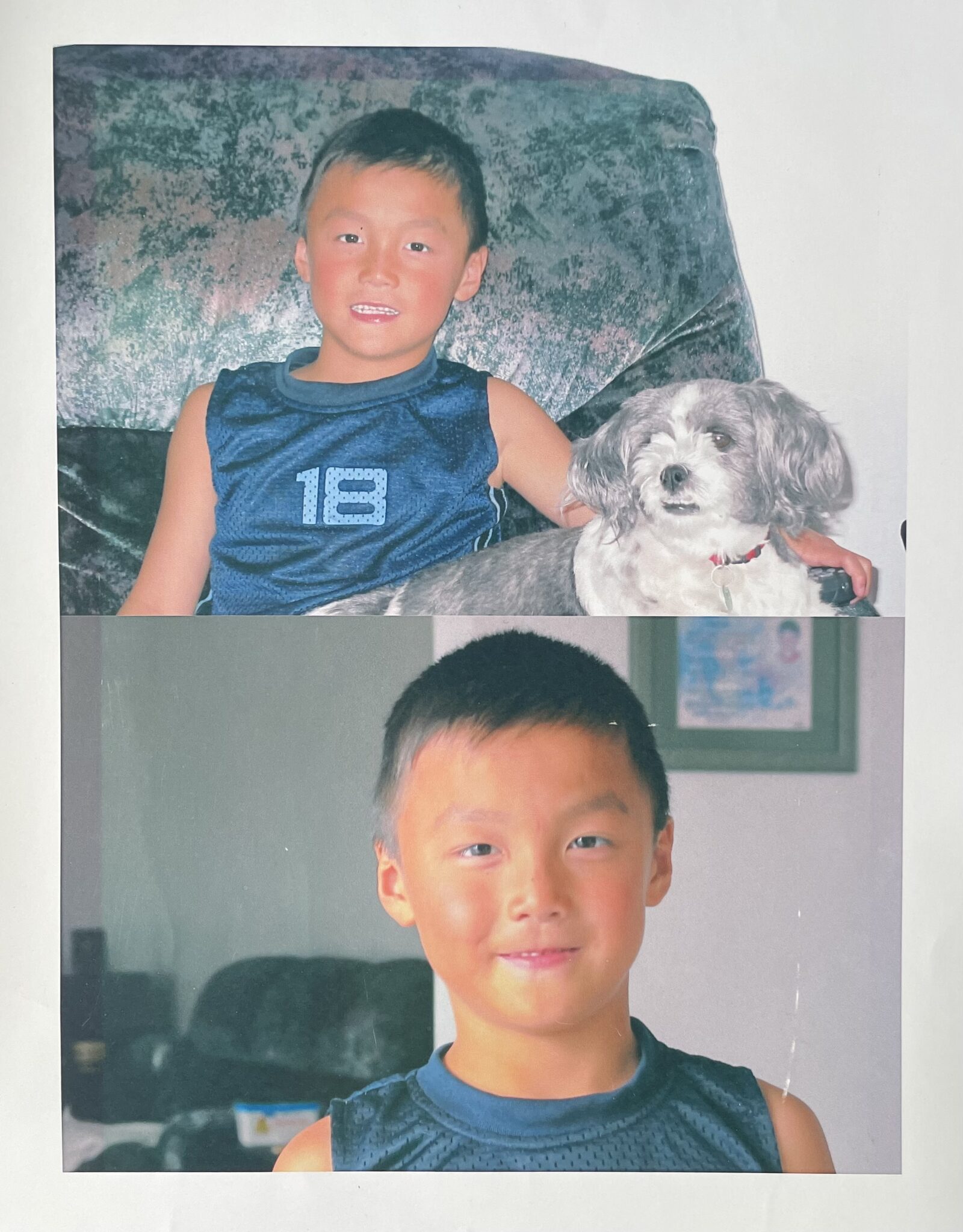

I was 12 years old, on route to a hockey tournament aboard a bus filled with teammates, coaches, and parents. It is no secret that kids tease one another, but from a young age, I knew there was something different about the “teasing” I received.

On this road trip, everyone was intrigued by PictoChat, a Nintendo DS digital communication app that allows users to connect by text and drawing.

At one point, I remember hearing someone begin to laugh. Eventually, the laughter spread to most of my peers and evolved into a roar. I thought, “why is everyone laughing?” When I looked around, I saw everyone’s eyes staring at their DSs and bursting out in laughter.

Naturally, I proceeded to find out what everyone was laughing at…

They were laughing at me.

The kids had been taking turns drawing racist pictures of me. I sat there scrolling through each drawing and message I had missed. I remember the grins on their faces and their eagerness to “one-up” the previous racist picture. I can remember them staring at me to see how I would react. Over a decade later, I can still feel the overwhelming emotions of humiliation, shame, and helplessness from that moment.

As the intensity of racist drawings and hate-filled laughter continued, my emotions became too much to handle, and I began to break down.

My tears began to flow, my body began to shake, and my speech was incomprehensible. My emotions and thoughts began to spiral. Why are they targetting me? Why is being Asian such a joke? There is nothing I can do about how I look.

Being Vietnamese sucks, I wish I looked like everyone else!

In a last-ditch effort for support, I jumped out of my seat and moved to the front of the bus, near all the adults. As I sat there weeping, I could still hear their hateful laughs coming from the back. At this moment, I remember thinking to myself,

is anyone going to do anything?

In the end, nothing was done.

When the dust had settled, and my tears had dried up, one of my peers approached me and said,

“I don’t know why you take everything to heart.”

These terrible experiences had tremendous impacts on my mental health. Situations like these contributed to my struggles with anxiety, self-esteem, confidence, and internalized racism (future blog post). It is important to understand that my experience and struggles are NOT isolated but shared by many.

Writing this story today, I am certain that any of the adults present at the time would have done something if they were aware of it. But the reality is they were not aware of it, and nothing was done. Unless we are willing to challenge our blindness, situations like mine will continue to be missed.

My story shows how colour blindness led to a lack of awareness, where teasing and racism were indistinguishable, and antiracist actions seemed unnecessary.

By refusing to see colour and not acknowledging BIPOC lived experiences, situations like mine will continue to happen.

Takeaway messages

• Colour blindness ideologies lead to a lack of awareness of racism and, ultimately, a lack of actions against racism.

• Experiences like my own happen every day. But challenging our “blindness” can help detect and reduce the occurrence of these harmful experiences.

My name is Miguel Jones and I am a Vietnamese transracial adoptee (TRA) currently living in Newfoundland & Labrador, Canada. In my blog titled "Miguel's World" I post about my experiences with racism, life coping with the autoimmune disease Lupus, and life as TRA.